EFTTappingPointsPetaStapleton.jpg

Image courtesy of Peta Stapleton

Fear of failure and emotional difficulties are common in high achieving students. This often results in self-handicapping and defensive pessimism, which leads to failure or lowered scholastic achievement (Martin, 2010). We know students who are engaged in content have better retention and improved problem solving skills. But students often face barriers that prevent active engagement learning such as stress. Stress has the potential to affect memory, concentration, and problem solving abilities that can then lead to decreased student engagement and self-directed learning.

Fortunately we also know that higher levels of self-esteem and resilience are shown to protect against fear of failure and emotional difficulties, and predict improved academic outcomes in both high school and university students. However few studies have investigated the efficacy of low-cost group intervention methods aimed at improving self-esteem and resilience in high achieving students.

This article outlines a non-randomized controlled clinical trial which represents the first Australian study of the efficacy of a group EFT (tapping) treatment program within two high schools. The trial aimed to increase student self-esteem and resilience, and decrease their fear of failure and emotional difficulties.

The technique

EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) or Tapping is a brief psychophysiological intervention combining elements of exposure and cognitive therapy, and somatic stimulation. It is often referred to as Tapping because it uses a two finger ‘tapping process’ with a cognitive statement. EFT is able to rapidly reduce the emotional impact of memories and incidents that trigger emotional distress, and is a powerful self-applied stress management method.

EFT has now been researched in more than 10 countries, by more than 60 investigators, whose results have been published in more than 20 different peer-reviewed journals (over 120 publications to date). Australian research has found EFT for obesity and food cravings (Stapleton, Sheldon, Porter and Whitty, 2011; Stapleton, Sheldon & Porter, 2012) and smoking (Stapleton, Porter & Sheldon, 2012) to be extremely successful and durable over time. EFT has been successful in treating a range of psychological conditions including generalized and specific anxiety, phobias, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), chronic pain, addiction, and emotional eating/obesity/food cravings (Church, 2013; Feinstein, 2012). Treatment length has typically varied between one and 10 sessions, with phobias effectively treated within one EFT session and PTSD requiring between four and 10. Research has also indicated treatment gains persist over time (Church, 2009, 2010, 2011; Rowe, 2005; Wells et al., 2003).

How does EFT work?

With roots in Eastern philosophies, particularly acupuncture, our understanding of how EFT works has been rapidly progressing. While initial explanations focused on the body’s “meridian” or energy system, tapping now has over a decade of clinical trials and research and these show this tapping technique has profound effects on the nervous system, the production of stress hormones (particularly cortisol), DNA regulation, and brain activation.

Performing the tapping while vocalizing aspects of a targeted problem (the cognitive element) decreases hyperarousal in the amygdala (the stress response area of the brain) and hippocampus (the memory area; Feinstein, 2010), alters dopamine and serotonin ratios (Feinstein, 2008), produces connective tissue transmission of piezoelectric signals (Oschman, 2006), and increases HPA axis regulation, which among other benefits reduces stress-related cortisol (Church, 2008).

The EFT process

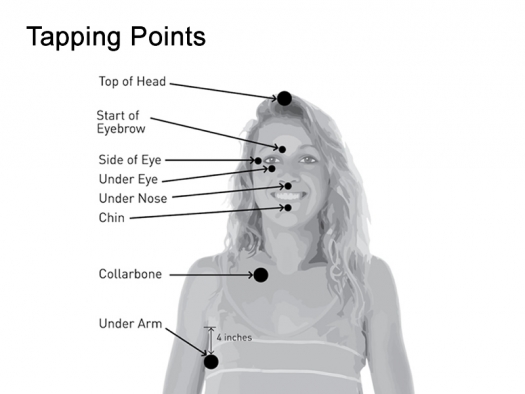

Rather than using acupuncture needles, EFT has clients tap, usually with two fingers, in the area of acupressure points on the face and upper body (see EFT points diagram).

The procedure of EFT begins by the individual stating a difficulty they are experiencing, followed by an opposing, but positive affirming statement. For example, an individual may state “Even though I am nervous right now, I accept myself and this problem.” Researchers have long found that when positive and negative thoughts are combined, the individual experiences a decrease of the negative experience (Kazdin & Wilcoxon, 1976). This combination of positive affirmation and negative thoughts is typically used in Systematic Desensitization, a behavior modification therapy (Kazdin & Wilcoxon, 1976).

The somatic component of EFT then involves tapping specific parts of the body (8 points are used on the face and upper body – see EFT points diagram) while saying a shorter reminder phrase, e.g. “nervous.” They rate the level of their problem (nervousness) out of 10 (0 = completely calm, 10=highest level possible of the issue) and re-rate this every time they complete the 8 tapping points. The process is repeated until the discomfort score is 0.

Evidence for students?

EFT as been investigated in many college trials, particularly for test anxiety, and has been compared to other approaches. In a comparison of EFT, a hybrid of EFT and EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing Therapy) and CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), both the hybrid and EFT achieved in two sessions each the same benefits as CBT did in five sessions (Benor et al., 2009).

In a comparison of EFT to sham tapping (unidentified acupuncture points) for stress in university students, the stress symptoms declined significantly more in the EFT group (by 39.3%) than they did in the sham tapping group (8.1% reduction; Rogers & Sears, 2015).

In a large study, American researchers examined 312 high school students and identified 70 of them with high-level text anxiety. They randomly assigned the students to a control group who received progressive muscle relaxation techniques or EFT treatment. While both groups reported a significant decrease in student anxiety, a greater decrease was observed for students who received EFT (Sezgin, Ozcan, & Church, 2009).

The school trial

I was personally approached by two schools in Australia, to run a trial. In total, 204 Year 10 students from two high schools participated: 80 were allocated to the EFT intervention group from school 1 and 124 from the second school acted as a waitlist control (they received the intervention at the end of the first group’s course). The average age of the students was 14.8 years and more than 50% were female. All students were engaged in academically advanced streams, and all EFT treatment was delivered in school time, with parental and school permission (and ethical approval from Bond University and the Queensland Government Department of Education, Training, and Employment).

The students all received five weekly sessions of 75 minutes each, during normal school hours and a booster session one year later. The facilitators were a registered clinical psychologist and a psychotherapist and both were qualified EFT practitioners.

All students completed the following measures at the start of the treatment, at the end, and at 6- and 12-month follow-up periods:

- Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

- Conners-Davidson Resilience Scale

- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for ages 11-17

- Performance Failure Appraisal Index-Short Form

- Weekly program evaluation + Family demographic questionnaire

The types of statements students used for the EFT process in the trial included common fears and beliefs raised by Martin (2010). Examples included:

- School is a waste of time.

- I can't do this.

- There's no point in trying.

- There's no way I can succeed.

- I might as well give up.

They also used EFT for three barriers to effectively using the technique:

- Forgetting to tap.

- Doubting that EFT can or will work.

- Becoming confused or frustrated with EFT.

EFT was used to target limiting beliefs and its application to areas such as academic and sporting performance:

- Success will make me stand out.

- Success will hurt my peer relationships.

- Success will put pressure on me to perform in future.

- I do not deserve success.

And finally, three other areas were addressed:

- Student's limiting expectations of themselves at school and in other areas of life.

- Perceptions of other people's expectations regarding participant behavior and achievements.

- Goal setting for the future, including doubts about achieving these goals.

The results

What was interesting was that the baseline resilience scores of the students indicated the presence of anxiety levels commonly found in populations suffering from generalized anxiety disorder. They also indicated their greatest concerns were a fear of failure, and self perceived difficulties.

After the 5-week program the analyses indicated a significant main effect of time for each of these: Difficulties and Fear of failure.

The largest statistically significant change was from pre-test to 12-month follow-up. Fear of failure was the most significantly affected variable, and students indicated in their survey a year later (compared to when they started the trial) that this was the most impacted area in their lives (a statistical difference indicates the results are not due to chance).

We concluded EFT has the potential to assist students’ perceived difficulties and impact their fear of failure in some students. Potential improvements in student functioning, ease of teaching EFT, and cost-effectiveness suggest that further research is warranted but EFT may offer students significant benefits with low risks and time demands, at relatively low economic cost to schools. This publication is now available: Effectiveness of a School-Based Emotional Freedom Techniques Intervention for Promoting Student Wellbeing.

Where to from here?

We have had much interest in the EFT program in schools since our trials, but have decided that conducting one-off trials may not be the most effective dissemination of the technique.

Tapping in the Classroom has evolved now as an evidence-based program designed to give teachers, school guidance counselors, psychologists and parents an effective tool to help students overcome stress, anxiety, and behavioral challenges in the classroom on a daily basis. The idea of using tapping in classrooms for everyday anxieties (e.g. nerves before an exam, excess tiredness after lunch) is proving to be a better option.

See Tapping in the Classroom for more information.

References

Benor, D. J., Ledger, K., Toussaint, L., Hett, G., & Zaccaro, D. (2009). Pilot study of Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT), Wholistic Hybrid derived from EMDR and EFT (WHEE) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for treatment of test anxiety in university students. Explore, 5(6), 338-340.

Church, D. (2013). Clinical EFT as an evidence-based practice for the treatment of psychological and physiological conditions. Scientific Research, 4, 645-654.

Church, D., & Brooks, A. J. (2010). The effect of a brief EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) self-intervention on anxiety, depression, pain and cravings in healthcare workers. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, 9(5), 40-44.

Church, D., Geronilla, L., & Dinter, I. (2009). Psychological symptom change in veterans after six sessions of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT): An observational study. [Electronic journal article]. International Journal of Healing and Caring, 9(1).

Church, D., Piña, O., Reategui, C., & Brooks, A. (2011). Single session reduction of the intensity of traumatic memories in abused adolescents after EFT: A randomized controlled pilot study. Traumatology. Advance online publication.

Craig, G. (2010). The EFT manual. Santa Rosa, CA: Energy Psychology Press.

Feinstein, D. (2008). Energy psychology: A review of the preliminary evidence. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, and Training, 45, 199-213. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.199

Feinstein, D. (2012). Acupoint stimulation in treating psychological disorders: Evidence of efficacy. Review of General Psychology, 4, 59-80.

Kazdin, A.E., & Wilcoxon, L.A. (1976). Systematic desentisation and non specific treatment effects: A methodolical evaluation. Psychological Bulletin, 83 (5), 729 – 758. doi 10.1037/0033-2909.83.5729

Martin, A. (2010). Building classroom success: eliminating academic fear and failure. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group

Oschman, J. (2006). Trauma energetics. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 10, 21.

Rogers, R., & Sears, S. (2015). Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) for stress in students: A randomized controlled dismantling study. Energy Psychology: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(2), 26-32. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2015.11.1.RR

Rowe, J. (2005). The effects of EFT on long-term psychological symptoms. Counselling and Clinical Psychology, 2, 104-111.

Sezgin, N., Ozcan, B., & Church, D. (2009). The effect of two psychophysiological techniques (Progressive Muscular Relaxation and Emotional Freedom Techniques) on test anxiety in high school students: A randomized blind controlled study. International Journal of Healing and Caring, 9.

Stapleton, P., Sheldon, T., Porter, B. (2012). Clinical benefits of emotional freedom techniques on food cravings as 12-months follow-up: A randomized controlled trial. Energy Psychology, 4, 1-12.

Stapleton, P. B., Sheldon, T., Porter, B., & Whitty, J. (2011). A randomized clinical trial of a meridian-based intervention for food cravings with six-month follow-up. Behaviour Change, 28, 1-16.

Wells, S., Polglase, K., Andrews, H. B., Carrington, P. & Baker, A. H. (2003). Evaluation of a meridian-based intervention, emotional freedom techniques (EFT), for reducing specific phobias of small animals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 943- 966.